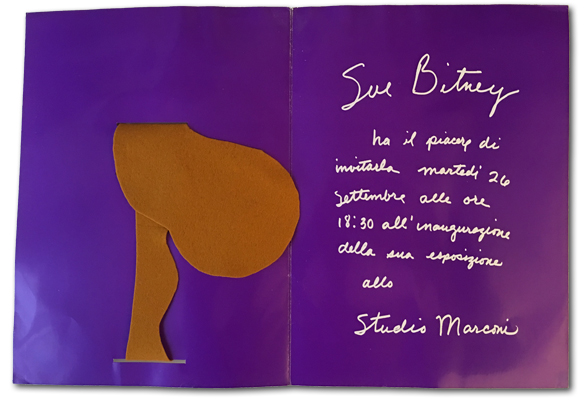

Sue Bitney Exhibition - Milan, 1967

This is the interior of the catalog produced by Studio Marconi to promote Sue Bitney’s exhibition.

Studio Marconi

Via Tadino, 15

Milano, Italia

Sue Bitney comes on strong for a chick. "Funk" is the quality in her work—a stylistic element that is almost impolite: tough, gritty and almost surreptitiously pungent. There are many "almosts" when talking about funk. It is elusive without being nebulous, like some hidden gamey odor in the work of art.

For no really convincing reasons that anyone has been able to produce, funk art has flowered in California, especially around the San Francisco Bay Area within the last few years. But the roots of this nightshade like phenomenon go back several years. Usually it has been the guys who were grinding out the funky work in the placidly hostile atmosphere of Northern California. The real scene, involving truly relevant artistic activity, came more and more to be centered around the artist's studios. And the art came more and more to manifest a common sensibility: it could be piercingly vigorous or outrageously ribald while remaining totally devoid of Fine Art's conventional self-consciousness. In general, funky art wasn't nice. So all the nice-nice people around San Francisco who use art as a convenient commodity with which to shore up their own social and cultural pretensions tended to turn their backs. Somehow funk art just didn't look right in the marble museum halls of Mammon's minions. This might have been the best thing to happen anyway, for America's would-be aristocracy of commercial mentalities has seldom been interested in developing that attitude of respect for the arts so fundamental to any civilized approach.

With their crass and callous power of cash, or with the brutal threat of censure, the Art Establishment first of all usually tries to tell the artist what to do. The best thing to happen to funk, then, was that it remained free from the patronisation of official acceptance without any understanding. With the beginnings of understanding came the discovery that funk art had the power to blow society's mind. Eventually, international recognition had to come to artists of major stature, such as Bruce Conner, Harold Paris and Peter Voulkos. This, in turn, led attention to a range of other California artists who slowly began to attract the attention they deserve. Among these, surprisingly, was Sue Bitney. This is unexpected because of that lingering something around the context of funk art—something just a little dirty, suggestive, tough and mean about it. And Sue is really quite nice. But the art! Like the rest of the funksters, her work has to be described-around, and all with unofficial terms, such as raucous and raunchy, or gutsy and goosey. It is not just out-and-out erotic representation—there is something more seditious and disarming. And that is what makes it all the more mind-blowing, when Sue Bitney comes along with sculpture to match the men, but then strikes the double low by adding a sweet smile.

En garde, Milano, for the sugar-coated, semi-sublimated violence that lurks in the loins and pervades the psyche of America. Funk is becoming respectable, which may be the cruelest ruse of all.

Kurt von Meier

September 1967

Two works by Sue Bitney circa 1967.

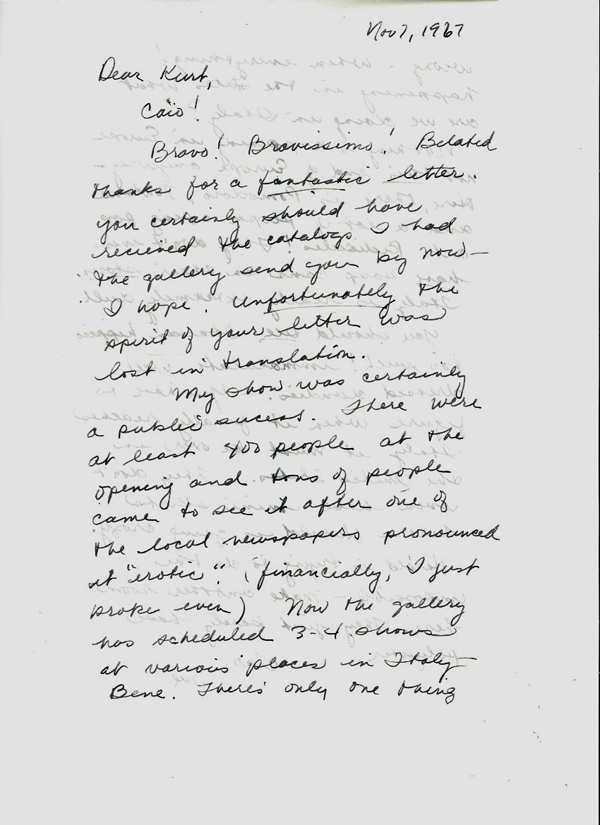

Below is a letter Sue Bitney sent to Kurt in November of 1967, thanking him for his commentary that was included in the Studio Marconi catalog and sharing her amusement at the appearance of Italy’s hippies, which she describes as “immaculate, well-dressed dandies.”