Los Angeles Letter: The Henri Matisse Retrospective - UCLA 1966

The Open Window, Collioure, 1914 by Henri Matisse.

ART INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE

LOS ANGELES LETTER - KURT VON MEIER

MARCH, 1966

A signal event of the young art year was the inauguration of the UCLA Art Galleries at the new Dickson Art Center with the Henri Matisse Retrospective 1966. Matisse supplies a very lovely and very safe subject; but at the same time the exhibition could have offered a more positive if not more prestigious contribution to the total Los Angeles art scene—in some ways already the most vigorous in America. The new Galleries emerge in topical conversation up and down the La Cienega art gallery row, in the context of such questions as: What are the implications of the Matisse Retrospective for the galleries' future exhibition policy? And further: What happens if even the newest university art galleries become dedicated to exhibitions that are rock-solid, however lovely, instead of breaking new ground with adventurous or even daring exhibitions that other institutions, more directly subject to the taste and politics of the vulgar, cannot or will not attempt? Answers to these questions may well prove crucial for Los Angeles in its accelerating rise from a provincial center to a city of cultural dominance.

Nymph in the Forest by Henri Matisse.

The Henri Matisse Retrospective 1966 was sponsored by the UCLA Arts Council, under the chairmanship of Mrs. Sidney F. Brody and Mrs. Herman Weiner, together with the Council's President, Mrs. Charles E. Ducommun and the Director of UCLA Art Galleries, Professor Frederick S. Wight. It will next travel to the Art Institute of Chicago and to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The introductory catalogue essay, unfortunately, is the largely irrelevant product of the imported talents of Professor Jean Leymarie. There is, after all, something to be said for looking at and writing about the works of art at hand, in preference to prosy, uncritical effusions about Matisse's eternal greatness; for if great he is, it has to be in the art. There is also an intelligent essay on Matisse's sculpture by Sir Herbert Read, and notes on Matisse as a draftsman by William S. Lieberman. The catalogue provides important illustrations of previously unpublished works, although these sadly lack adequate documentation; there is a helpful supplement to the bibliography already available in Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Matisse, His Art and His Public (New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1951), which remains the basic book.

The exhibition contains some magnificent works which will prove important for students and for the West Coast public who, even with the 1952 Los Angeles Matisse exhibition, will not have seen works in the recent large Matisse retrospectives: of 1951 at the Museum of Modern Art (nor, indeed, the retrospective there twenty years earlier), of 1948 at Philadelphia, or of 1956 at Paris. Whether or not Matisse needed another retrospective now may remain an open question, but given the exhibition, the old problem of having cake and eating it too comes up. Among the key works mentioned in Leymarie's essay are the following : Dinner Table, 1897 ("a landmark") ; Luxe, calme et volupté, 1904-05 (a "painting-cummanifesto") ; The Green Line ( Madame Matisse), 1905 ("in which the grandeur and unity of the new style are mastered ") ; Joy of Life, 1905-06 ("at once the symbol and triumphant condensation of Matisse's art and the first supreme monument of our century") ; Blue Nude, 1907 ("formidable") ; Interior with Eggplants, The Blue Window, and The Painter's Family, all of 1911, and all of which Leymarie writes about at length. Yet despite this attention not one of these works (and there are more) has been included in the exhibition. Now either these are not such important works after all, or Leymarie tends to diminish the significance of the retrospective by writing about them rather than about the works that are included.

Woman with a Turban by Henri Matisse.

To some extent this criticism is mitigated by the continued lack of cooperation on the part of the Barnes Foundation of Merion, Pennsylvania, and the art authorities of the Soviet Union, who each control Matisse collections among the finest and most important in the world. Yet, despite such absences there are nevertheless gathered here some individual works which stimulate a new look at Matisse.

The Open Window, Collioure, 1914, is among the most astounding of these, although it goes unmentioned by Leymarie. Apparently Matisse over-painted the central portion, as indications of what might have represented a balcony railing can be detected under the wide black stripe. Results of ultraviolet and X-ray examination of this painting (and of others as well) would have provided a most important contribution to scholarship by their inclusion in the catalogue. But whether over-painted or unfinished, the painting does exist. The brown window sill along the lower edge of the canvas and the angles of some cast shadows give away Matisse's illusionistic intent, an essential distinction between this and the later painting of Rothko, Newman, Louis, or the work of the young Massachusetts painter, Beau Egan. But if Matisse does not here provide source material in the same sense as Mondrian did, he nevertheless demonstrates an extra‑ordinary early concern with the aesthetic and formal problems raised in different ways by the work of these later artists. For no matter how unlikely at the time (1914), or indeed for Matisse at any time, here we have an extreme statement of some essential problems: subtle and mean color in contrast to sweetness and light, grossly simplified pictorial structure in contrast to infatuation with the arabesque, the idea of pictorial solidity taken further than Cezanne and thus contradicting him, and composition in terms of strong vertical elements. The concern of Matisse with these problems is well established by the contemporary Paris and Issy-les-Moulineaux works: the Phillips Collection's Studio, Quai St. Michel, 1916, the Tate Gallery's The Painter and his Model, 1917, or the earlier Goldfish in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel A. Marx.

Although it is unsigned, The Open Window, Collioure is a beautiful and significant painting when we look at it this way—its ambiguous state of completeness perhaps even contributing to the unequivocality of its statements. In the end it may not be possible to avoid the problems of the non finito; but even so, impressive paintings such as Nymph in the Forest, 1936 (sic!), or Woman with a Turban, 1929-30, demand to be approached with at least as much attention as the more so-called finished works of art. Matisse's working method of conceptual and visual reduction was usually coupled with a propensity for ornamentation; together they posed a constant inherent threat of overworking a piece. These "unfinished" works are finished when we say they are, and as such provide illuminating comparisons with other oils (sometimes greater, but also sometimes overstated), and particularly with his pure and brilliant graphics.

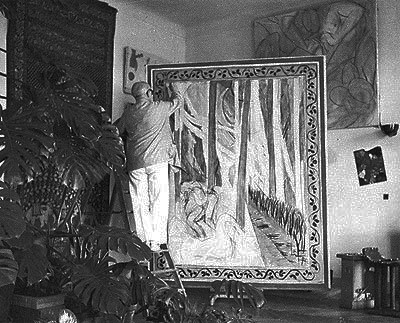

Varian Fry's photograph of Matisse at work on a painting (1941).

Again, it is unfortunate that these paintings do not receive the attention they deserve in a major retrospective, for they sometimes raise far-reaching questions in the minds of students, scholars, and museum visitors in general. An example of such complications is provided by Nymph in the Forest, dated 1936 by the catalogue (No. 74, pp. 100, 191). To the same painting, however, Barr gives the title Nymph and Faun, a subject Matisse had earlier explored around 1909. Barr identifies the subject matter as "a faun playing his double pipes to a sleeping nymph" (p. 257). He also publishes a photograph taken by Varian Fry about August, 1941, showing Matisse at work on the painting, intended, Barr suggests, as a tapestry cartoon. "The tapestry itself never seems to have been woven although the cartoon appears to have been intended as a design for a pendant to the Window at Tahiti tapestry of 1936" (p. 278). At last, this seems to explain the UCLA catalogue's date of 1936, while still overlooking the photographic evidence of 1941. This is further complicated by the fact that Matisse presumably painted out the border design seen in Fry's photograph at an even later time. But without all this information, it would be difficult for the average visitor to understand that both publications actually refer to the same work. For the student it is still more difficult, as important problems are obscured, such as those of variant titles, dates, interpretations of subject matter, intent or relationship to other paintings and projects, and pentimenti, or the many changes made by Matisse as the painting progressed.

In challenging Barr's dates and titles, however, none of these or similar problems is even hinted at. But perhaps this is a straw in the wind: a small scale indication of a vast and pervasive phenomenon, affecting the organization, nature, and ultimate significance of many exhibitions, not only in Los Angeles, but throughout the world. There appears to be a slow but distinct shift in the function and status of professional people in the world of art. Directors, curators, installers, art historians and critics are all having their positions modified, for better or worse, by the expanding power and influence of the patron and, in both the good and the bad sense of the term, the dilettante.

The effects of this trend are perhaps more readily apparent in Los Angeles than elsewhere because of the rapid development and proliferation of museums, galleries, and other institutions with interests devoted to the arts. Some rather violent effects of the amateur's power in its confrontation with professional standards and practices, for example, have been felt in the continuing controversy that has followed Dr. Richard F. Brown's resignation as Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art six months after it opened. More positive effects, however, include the many and increasingly generous examples of sponsorship and public support for exhibitions and other activities related to the arts.

**********

L Red by Kenneth Price.

Further evidence of Southern California's vigorous growth is the opening of a second gallery connected with the University of California. Under the directorship of John Coplans, the art gallery of the Irvine campus is located on the fringe of Los Angeles, about fifty miles to the south. After a fine exhibition of twentieth-century sculpture drawn predominantly from collections in the Los Angeles area, and the showing of a lithograph series by Barnett Newman in conjunction with the Nicholas Wilder Gallery, Coplans brought together, in spite of modest resources, an incisive and exciting exhibition, Five Los Angeles Sculptors.

The Sorcerer by sculptor Tony DeLap.

Kenneth Price's pieces in brightly polychromed fired clay are excellent embodiments of the Aesthetics of Nastiness—a phenomenon of penetrating and widespread (if as yet largely unstudied) significance, especially on the West Coast. The other four sculptors, on at least a superficial basis, seem to group together more coherently as representatives of the Fetish Finish, clean edge, L. A. Cool School. Closely set in chrome-plated metal frames are Larry Bell's three boxes of coated glass. These were included, with other related pieces, in Bell's recent one-man exhibition at the Ferus Gallery. The larger translucent and partially mirrored cube structures most effectively achieve the illusion of topless (baseless and side-less) sculpture. The problem of limits is extended philosophically as Art and Life interpenetrate when dimly visible objects or people pass behind the pieces; and at the same time, the world behind the viewer is partly reflected by the surfaces. These ambiguities of mass and space are then compounded by interior reflections which produce the old fun house or infinite barber–chair effect. As did Bell, Tony DeLap helped to represent the United States at last year's Sao Paulo Bienal, together with the Los Angeles painters Robert Irwin and Billy Al Bengston, and four other artists. The most complete realization of the direction in which DeLap has grown since that exhibition is seen here in The Sorcerer, a looping structure of wood, brass, and laquer. Related pieces such as Ka, of laquered fibreglass and stainless steel, were recently shown at the Felix Laudau Gallery, and are now scheduled at New York's Robert Elkon Gallery. In DeLap's small cast aluminum piece Bunco, a baseless, square cross-section rod, bent into three dimensions, fascinatingly shifts its character when viewed in its several possible resting positions, suggesting a direction formally related to the current work of young British sculptors. David Gray, currently having a one-man show at the Ferus Gallery, manifests in his work a Cold Expressionism permeated by a sense of hospital evil—really perhaps another facet of the complex Aesthetics of Nastiness.

Yellow Pyramid by John McCracken.

The most exquisite and exciting of the five sculptors at Irvine is John McCracken, who included two large pieces of plywood, fiberglass, and epoxy paints, built up like macro jewellery and, finally, with automotive laquer, finished like a Ferrari fender. At the Nicholas Wilder Gallery in June, 1965, McCracken showed several superbly crafted rectangular boxes with precise slots or elegant curves sliced out of their fronts. In this more recent work he has retained his remarkable sense for appropriate color, while further refining the sculpture's structure and finish, and considerably expanding its scale. Yellow Pyramid is six feet square at the base and four feet high, while Blue Post and Lintel, now in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Frederick R. Weisman, towers eight feet six inches high. McCracken's work is healthy, imposing, and tough, both aesthetically and literally, avoiding finally the anticipated associations of preciousness by the very fact that, although elegant, it can be placed outside as easily as any automobile. It also challenges the concept of Impersonality, so important one way or another in the analysis of most contemporary West Coast art. Really astute examination of the pieces reveals the traces of intensely personal attention in their making. Of course tools are used in the process—a whole rack of them—but the open question that remains is, "To what extent have these now become creative extensions of the sculptor's own hands ?" Within the subtlety of minor variations we may even discover evidence of something very human that can only inadequately be referred to as love.

An excellent adjoining section of the show presents sculptors' drawings, adding to work by the above artists that by Judy Gerowitz, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris.

**********

Four Cones by artist Wayne Thiebaud.

A few miles from Irvine, at the Balboa Pavilion Gallery, Sterling Holloway organized for Christmastide a unique exhibition of sculpture, painting and graphics, Especially for Children. A fine example of what non-professional enthusiasm can achieve, actor and collector Holloway gathered a colorful assortment of works from both individuals and institutions. The outstanding selections, in addition to kinetic sculpture by Charles Mattox and boxes by Cornell and Trova, included samples of child-food art: 4 Cones and a Gumball Machine by Wayne Thiebaud, Sundae by Claes Oldenburg, Joe Goode's milk bottle painting Happy Birthday, Olodort's Hamburger in the Rain, and Peanuts by Charles Schultz. Delicately lovely, yet with an undertone of uncompromising meanness, are the strange and impressive drawings and paintings of clouds also by Joe Goode.

In January this exhibition moved to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art where, for the first time in the city, there could be seen the recent overwhelming work of Harold Paris. A pair of rooms entitled Pantomina Enfanta was created especially for Holloway's show. Black rubber floors, black walls and surfaces, structures, cast or modelled forms in rubber, wood and plaster, all contributed to a compellingly powerful almost surreal effect. For adults, especially, this work is not easy to approach, and Holloway should be commended for his courage in presenting it—although, interestingly enough, children seemed to have little trouble discovering the tactile and visual qualities Paris has so carefully formulated. This is first-rate work; and on this basis alone—although he has constructed two other larger Pantominas —Paris establishes himself among the most brilliant, inventive, and daring sculptors at work anywhere.

**********

Also recently at the County Museum was Art Treasures from Japan, an uneven assemblage, sometimes sumptuous however, and containing inter alia some magnificent and historically important individual pieces; and Five Younger Los Angeles Artists, which included Llyn Foulkes, Lloyd Hamrol, Philip Rich, Tony Berlant, and Melvin Edwards in a mixed bag (and not all brand new). Foulkes is rapidly, if inadvertently, finding himself Master of the Postcard, as the great postcard-image paintings inspire a growing, perhaps quasi-camp, cult of exchanging by mail open-faced "refs", or references to culturally significant trivia. Hamrol, who with Foulkes shows at the Rolf Nelson Gallery, explores and refines in sculpture the implications of environmental space, with less dread than the Pantomina of Paris. Instead, he parallels the austerity and clean form qualities of Bell, Gray, DeLap, and McCracken.

Sculptures in David Smith's CUBI series.

With unplanned tragic irony two major exhibitions of sculpture at the County Museum were transformed into commemoratives just before their respective openings. Following David Smith's death last May in an automobile crash, Maurice Tuchman (who together with Smith himself had selected fourteen of what were to be his last pieces) presented David Smith: A Memorial Exhibition in November. The catalogue shows the large, burnished, stainless steel Cubi series in its pastoral setting outside Smith's studio at Bolton Landing, New York. But the installation at Los Angeles questions the relationship between essentially human-scaled contemporary sculpture, and (perhaps unconsciously surrealist) essentially inhuman-scaled contemporary architecture. The most effective pieces in the exhibition are those like Cubi XXI, set in the moat and visually buffered by water; but this is purchased at a high price in terms of the severe and unfair limitations of approach placed upon the viewer. Even the enormous strength of Cubi XXIII, one of Smith's most successful works, is sapped by the unremitting expanse of architect Pereira's Simon Sculpture Plaza. These problems were also raised last year when some of Smith's Cubi sculptures were installed (and then visually lost) in the sculpture courtyard of New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Some other problems raised by the David Smith exhibition: How well does his dark line graphic effect really work (where the stainless steel planes are welded together)? Is there any convincing aesthetic relationship between the cleanly conceived and geometry-derived sculptural masses and the calligraphic, "expressionist" burnishing on their surfaces? How close to indestructability does sculpture have to become before we can touch it, sit on it, walk through it, or caress it? And who actually makes the decisions that prevent us from so doing? What would David Smith have said about all this? And is this, or is this not another multi-level example of the Art : Life problem posed penetratingly by Oscar Wilde and developed by the genius of Duchamp?

Inside the County Museum's Lytton Gallery adjoining the plaza is, through February, the West Coast version of the Alberto Giacometti retrospective organized by Peter Selz for the Museum of Modern Art. With news of the Swiss sculptor's death on the show's preview evening, this again became, in effect, a memorial occasion. Los Angeles now finds itself with the imposing task of reevaluating Giacometti's total achievement at this particularly difficult time.

The Couple by Alberto Giacometti

Without space here to consider why it is so, Giacometti's painting is quintessentially sculptor's painting, subject to severe, self-imposed limitations, and thus in some ways seems vastly overrated. Giacometti's sculpture separates itself into two general periods, the chronological divide being his return to figural subjects around 1936, which was followed by his increasingly single-image concentration. A reconsideration of the lingering problems associated with New Figurative art are more convincingly prompted by stylistic qualities of loneliness or anguish in Giacometti's work than, for example, by the work of John Paul Jones, a retrospective exhibition of whose paintings hung in the same gallery before the Giacometti show arrived. This change in subject matter also represents a crucial and paradoxical shift in Giacometti's approach; later conceiving the medium of sculpture itself as process and reality, from his earlier conception of sculpture as the process whereby works of art are produced. This is manifest in his shift from fantastic or Surrealist subjects, conceived traditionally as sculptural images or entities, to highly traditional subject matter (the academic single standing nude human figure) conceived radically as magic and "primitive" art, or in the anti-masterpiece sense of oeuvre-totality. Thus it is difficult to justify discussion of any one (rather than any other) single piece made by Giacometti during the last thirty years. Instead we are ultimately forced to consider the complete oeuvre integrally. But this is not essential to the approach of Giacometti's amazing and beautiful work created during the preceding decade (1925-35). Unfortunately, some of the most important of these early pieces have been listed in the catalogue but have not been sent to Los Angeles : Disagreeable Object, 1931; Hand Caught by a Finger, 1932; No More Play, 1933; and the well-known structure The Palace at 4 A. M., 1932-33. Two of the works included, however, provide clues to the figure-icon fixation that drives and dominates Giacometti's later work. The Couple, 1926, has clear stylistic relations to West African wood sculpture (compare the Dogon couple illustrated by J. J. Sweeney, African Folktales and Sculpture, Bollingen Series XXXII, New York, 1952 and 1964, plates 40 and 41) ; and The Spoon Woman, 1926, assumes the same severe and magical majesty as the highly stylized Cycladic marble figures from the third millenium B.C. In Giacometti's late totemic figures not only are the human proportions thinned and elongated (Wilhelm Lehmbruck and Gothic sculptors before him had done that), Giacometti also utilizes a highly sophisticated scheme of perspective/distortion. If his Tall Figures are viewed di sotto in su with the feet at eye level, and up close, a consistent three-dimensional perspective-based illusionism makes the pieces appear to be two or three times their actual height. In this way their real iconic monumentality is most convincingly apparent.

Big Blue by Ron Davis

In brief, the exhibitions in Los Angeles of work by the following artists must be mentioned : Arlo Acton's swinging, funky, and some say typically San Francisco-style aluminum, wood, and what-not sculpture at the Nicholas Wilder Gallery. There also Agnes Martin showed ethereal, seductive canvases, and Ron Davis presented a series of relief-paintings which deserve in the future far more serious critical attention. They involve intricate problems of perspective and isometric projections; and his Big Black is one of the most commanding paintings of the year to have been created in the Los Angeles area. Edward Kienholz wittily erected his Barney's Beanery tableau in Barney's Beanery, before it traveled to the Dwan Gallery in New York and was subsequently apotheosized in Time. Kosso's I-beam sculptures were impressive at the David Stuart Gallery. Mark di Suvero and a battery of assistants took two weeks to erect two huge pieces (Nova Albion, 18 1/2 x 28 feet, and the smaller Pre-Columbian, only 8 x 16 feet) inside the Los Angeles Dwan Gallery—in the process necessarily chopping a hole through the ceiling. Richard Pettibone's exhibition of portraits of collections of paintings at the Ferus Gallery requires (and deserves) a separate article. These miniature versions of the modern masters as interpreted by ex-model plane builder Pettibone extend the conceptual and aesthetic issues of Reality in Art and Life perhaps with more immediate relevance than any work since Abstract Expressionism, and with more intelligence than any work since Marcel Duchamp.

A final note should be devoted to the stimulating photographic work of Robert Heinecken, who presented forty pieces in a recent three-man show at the Long Beach City Art Gallery. His fortcoming one-man show at Cal State, Los Angeles, should provide opportunities for a fuller discussion of such fascinating pieces as the Square Multiple Solution Puzzle, the title of which inadvertently sums up so much of what is going on elsewhere on the West Coast scene.

Kurt von Meier

This is the cover of the March, 1966 edition of Art International, in which this article appeared. Art International discontinued publication in 1984. Kurt was a regular contributor during the years 1966-67.